A tradition dating back 12 centuries

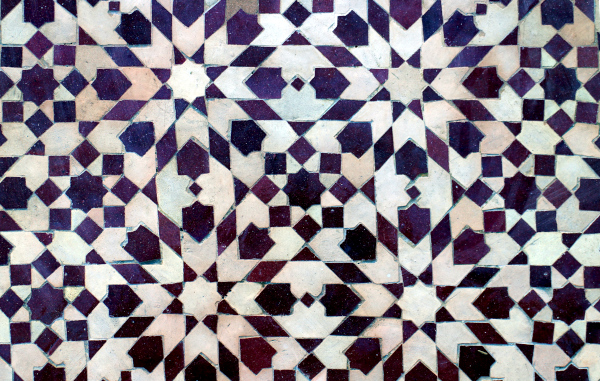

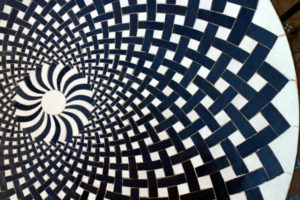

Zellige is the name given to the ornate and colourful mosaics that can be admired in many elegant buildings around North Africa and the Middle East.

The craft originated in Fez, Morocco, in the late 8th century and it still practiced today by master artisans. Small pieces of colourful tile are cut by hand out of glazed ceramic tiles, using a fine chisel, and then set into white plaster to create intricate designs.

In accordance with Islamic principles, only geometric patterns are created.

Because many Muslims fear that the depiction of the human form is idolatry and thereby a sin against God, it is forbidden in the Qur’an. Islamic art, therefore, has focused on the depiction of geometric or floral patterns and Arabic calligraphy rather than on shapes of living creatures.

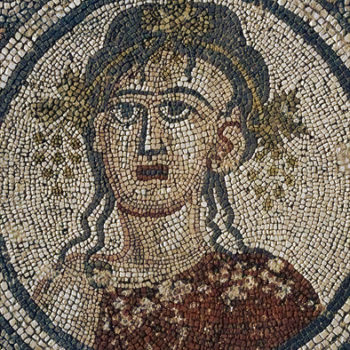

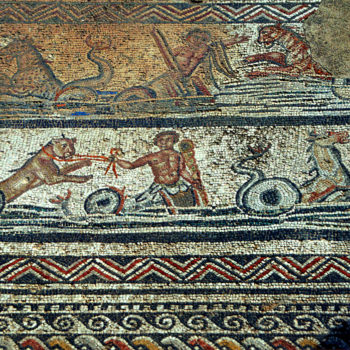

Beside visiting the Roman Volubilis during my stay in Fes last December I wanted to learn about this ancestral craft. I was lucky to be able to visit one of the schools where young people learn the craft.

5 years to train a skilled craftsman

Cutting the zellige tiles, a skill handed down from father to son, requires intense training and hard work with low pay. Few young people now are interested in learning how, as factories here and abroad can spit out similar tiles much faster and cheaper.

The craftsmen I met may be part of the dying breed. They crouch in a noisy and dusty workshop, their knees resting on stones or concrete blocks.

Their laps protected by a piece of fabric, they cut the tiles with tools very similar to the ones Roman mosaicists used 2000 years ago and I still use in my shop in Alabama.

They methodically cut intricate chunks of colored clay between their chiselling hammer (Italian martellina) and a sharp anvil (tagliolo)

Will the craft survive ?

It takes 5 years to train an apprentice and many more to train a master. Today, few young people are interested in learning the craft. The government of Morocco, aware of the importance of reserving such unique cultural asset, has opened several schools to keep the traditions alive. But for 4 actual working craftsmen, only one is being trained. Unless people from the young generation can make a good living out of this difficult job, the craft may die with their fathers.

Survival of ancestral techniques is not a given. Will Morocco be able to preserve the craft of Zellige makers ? Will Portugal be able to preserve the knowhow of its calceiteiros ?

In my native Picardie, until the 1950’s a few craftsmen were still able to shape cubes out of flintstone to build walls. To my knowledge this craft has been lost.